Why English Is A Weird Language

After learning English as a child, picking up German an der Universität, and trying to learn French aprés - something feels off in continental European languages. Not harder exactly - just different. This post explains why

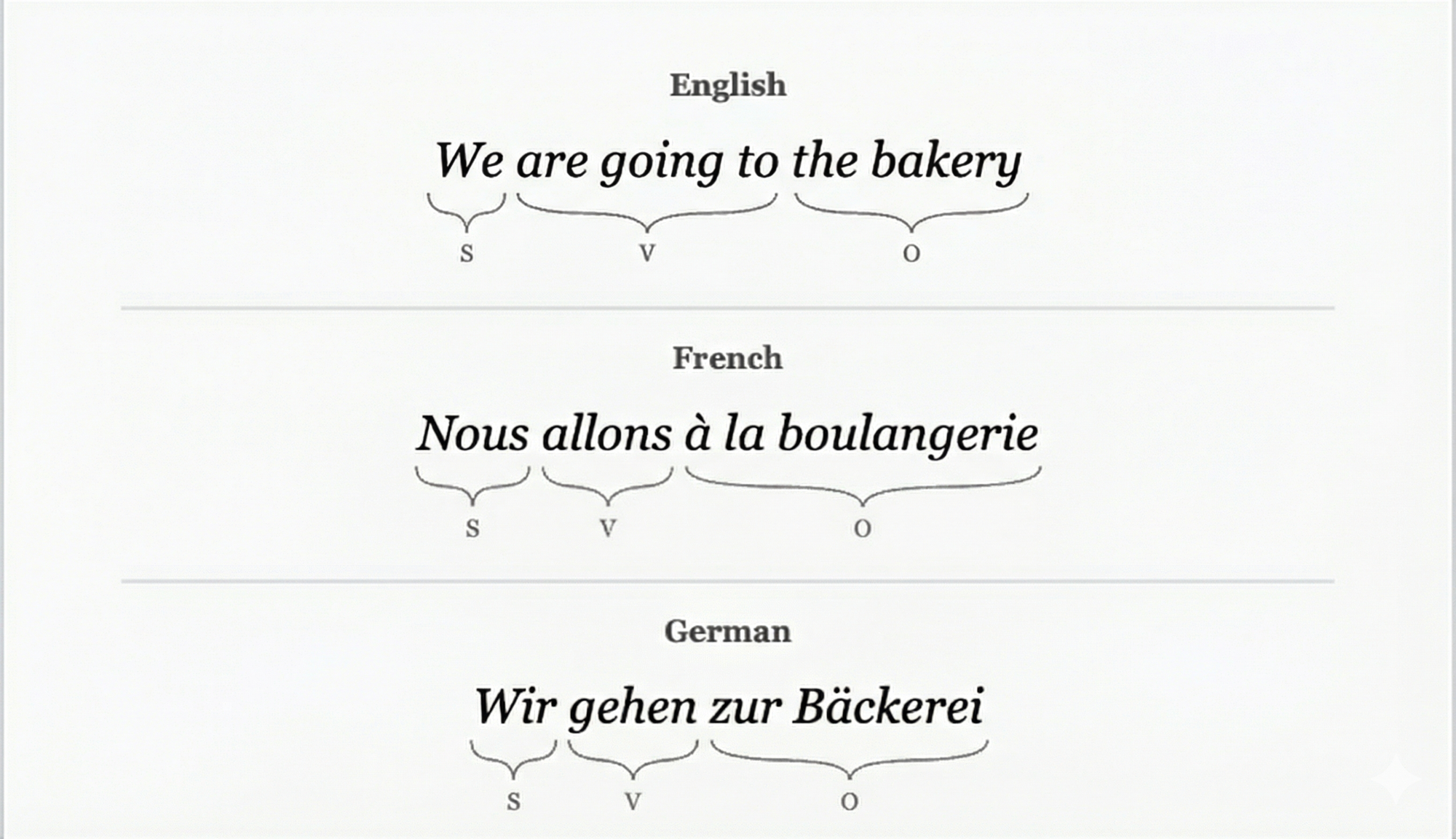

After learning English as a child, picking up German an der Universität, and trying to learn French aprés - something feels off in continental European languages. Not harder exactly - just different. The words don't slot together the way you expect. Let's take something simple: "We are going to the bakery."

- English: We are going to the bakery

- French: Nous allons à la boulangerie (literally: we go to the bakery)

- German: Wir gehen zur Bäckerei (literally: we go to-the bakery)

All three follow Subject-Verb-Object order. But look at how many words English needs to say the same thing. French and German each use one verb. English uses three words: "are going to." This pattern runs deep. English constantly inserts helper words - do, does, did, am, is, are, will, would, have, has - where other languages just use the main verb.

English can't just invert the subject and verb like German and French do. It needs "do" or "are" to make the question work:

- German: Gehst du? (Go you?)

- French: Tu vas? (You go?)

- English: Do you go? or Are you going?

German puts "not" after the verb. French wraps the verb in "ne...pas". English brings in "do" just to carry the negative:

- German: Ich weiß (ß is pronounced as a double s) nicht (I know not)

- French: Je ne sais pas (I not know not)

- English: I don't (do not) know

How English Got This Way

English started as a Germanic language with a verb system much like German's. You could say "Know you this?" and "I know not" and everyone understood. Then 1066 happened. The Norman Conquest brought French-speaking rulers to England. For centuries, the aristocracy spoke French while common people spoke English. The languages mixed, and English grammar simplified dramatically.

As the old verb forms eroded, English needed new ways to express tense, questions, and negatives. The solution? Auxiliary verbs. "Do" became a grammatical Swiss Army knife. "Be" expanded to create continuous tenses that German and French don't have. "Will" took over future expressions. The result is a language where the core SVO structure gets mixed with helper words that other European languages don't need.

When you learn German or French, you're learning languages that kept their verbs intact. Gehst du zum Bäcker? is four words. Are you going to the bakery? is six. German packs more meaning into fewer words because the verb carries the semantics. This tradeoff shaped how each language thinks. German and French speakers learn to listen for verb endings - those endings tell you who's doing what and when. English speakers learn to listen for helper words instead.

When German or French word order feels alien, you're not struggling with complexity. You're unlearning the auxiliary habit English trained into you. Once you stop reaching for "do" and "are" and let the main verb do its job, these languages start clicking.